1.

. . . And he told them he didn’t do portraits.

They asked him why, and he said because

the last time he did a portrait he was

screamed at by the model who claimed

he didn’t capture the true her.

As if she might’ve had some clue

as to what that was. See, when the work

gets too personal for anyone else besides him,

that’s when he always gets into trouble.

And there are all the little ulteriors that

hang in the balance, besides.

So he doesn’t do them.

But this family wouldn’t leave him alone.

And it’s not as if he doesn’t like to be begged.

Who doesn’t?

But these people were REALLY trying to

twist at his heartstrings.

They said the portrait was in memory of their dead mother.

Oh, boo hoo.

And when that didn’t work – sentimentality rarely does with him –

then they tried to yank on his empty pockets

with offers of ungodly amounts of money.

And that is where he fell.

It’s where he always falls.

Plus, they were able to convince him,

gullible fool that he can be,

that a dead woman could hardly

scream at him about a job not well done.

So they all shook hands, and the process began.

An impossible one, he would later come to find,

but then he’s always been of the opinion that

Creation is a job for someone with at least

a high school diploma or the equivalency.

And at all times requires a crash helmet.

2.

. . . How had he let himself fall for it again?

How do you paint someone you don’t know?

Because, you see, it isn’t just a face you paint. It’s a spirit.

An energy.

So, faced with that puzzle, and since he didn’t know the dead woman personally,

he decided he would do everything he could think of to learn about her life.

He started gathering, collecting, rallying around him all the trinkets that spelled her life.

Anything her family could possibly dig up.

Photographs. Letters. A handkerchief bearing the scent of

lilacs and mothballs. Very telling, that one.

Purses with lipsticks glued inside.

There was a pair of old nylons,

never worn, just packed neatly away in a rusted hope chest.

A brooch of black pearls and emeralds.

Most of the emeralds missing.

A very badly tarnished silver teething cup

with a name inscribed. Hmmmm. Laura.

Just like the movie.

A dead rose from Laura’s funeral, which someone had

flattened between the pages of

Psalms and Proverbs.

And an old, musty, floral-printed dress.

He placed every bauble and memory on tables and chairs all around him,

And just sat for days,

staring at the stained wallpaper,

feeling a bit like the irascible Raskolnikov.

He held in his hand the dead woman’s hair brush,

all ensconced in tangled and mangled

grey and black hairs.

Slowly he lifted it to his nose to smell.

Only hair. Nothing special.

You know, what can you really get from hair?

Maybe a hint of old, stale Bergamot.

Just trying to get acquainted.

He felt like he was on a first date.

What the hell. He popped a few Black Mollies and started.

But to his hallucinogenic dismay, his first stroke was weak –

ignorant – uncommitted – bullshit!

The color was wrong, the light was wrong, the intent was wrong.

So he threw it out, and sat three more days.

He had run through every canvas and every little tube of his oils

trying to express dead Laura. Then he couldn’t even afford to

re-stock his supplies!

So in pure and pissed-off desperation, he thought to his huffing self,

I will slit my wrists if I have to,

and paint her on the walls with my own blood!

The truth is, it’s just too goddamned expensive to be a starving artist these days.

And a good dental plan certainly couldn’t hurt to make it a more sought-after position.

3.

. . . So he just sat.

For days upon days with the sights and smells of dead Laura.

Reading her letters, memorizing her penmanship, sleeping with her quilt draped over his legs.

He paced his flat for countless unbathed, sweaty days,

and went through several fifths and an easy carton of Marlboros.

He listened to the weeping timbre of Callas on an old turntable, because that voice was how he felt.

Until one day, out of the blue, after all of the madness,

for mad was what he had become,

he suddenly realized – he was wearing her.

Laura.

As one puts on a cloak and lavishes in its feel, so he wore her very life on his ripe body.

It hung from his limbs, perhaps a little snug in the arms,

but every part of her was now in his grasp. Every little nuance.

He knew her better than he knew himself.

He was a bit awed and trembling, but needed to shake it off so that he could keep going

and actually get some paint to canvas.

He immediately hastened to the business of stretching a canvas on a 10 ft. x 10 ft. frame.

So huge and unmanageable was the thing that he had to literally lie on top of it.

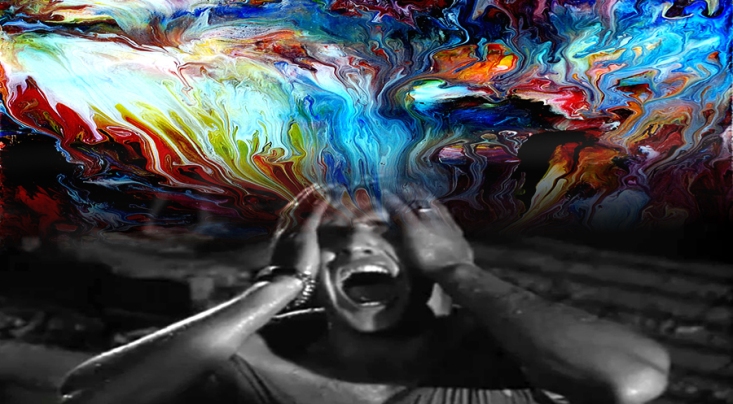

He mixed paints with such a flurry that he stumbled clops of swirly color onto the canvas

before it had even been given the chance to be completely mixed,

so much faster did his head work than his hands.

He painted her with a fever by day, and with a pitch by night.

Hues of every conceivable shading and variation surfaced.

Thoughts toppled over one another to get to the canvas.

And a sort of unhinged randomness became his M.O.

For twenty-three haunted days of glorious, glorious madness

he pranced and flung paint to the round-the-clock screams of Fishbone

(he had long, by this point, abandoned Callas)

and a half pint of Old Forester.

And it was – a masterpiece.

Was he even allowed to feel that?

Somehow, he didn’t care.

He circled it for fear that he’d dreamt it. But it was real.

And he breathed in the smell of her, which was beyond the pungent turpentine, stale bourbon, and cigarette smoke.

He stared at her until she bewitched him, and he would be so bewitched.

She was strong, yet sad and eloquent, just like her love letters.

And angry too, like that cracked hand-mirror that he could just see her

dashing against a wall.

Yet vulnerable, as in the melancholy eyes that graced every one of her photographs.

But most of all . . .

Well, look for yourself.

Is she not the most exquisite beauty you have ever seen?

It probably comes as no surprise by now that he had

fallen in love with Laura.

The minor detail that she was dead didn’t seem to stop that

ball from dropping, did it?

So the cliché IS true. All artists do fall in love with their models.

Even the expired ones.

This career is definitely not for the faint of heart.

4.

. . . And then as if the laws of fate weren’t already

finding him the perfect punch line to a joke,

the family of dead Laura was not, as it turns out,

especially thrilled with his portrait after all.

Idiot! (This was to him, not them)

He should know better.

How many times in the past had he already walked into this trap?

See, they wanted something they could put on their mantle like a holy shrine,

to decorate with flowers.

They weren’t interested in something they might have to ponder!

They wanted something they could readily identify.

Like a police sketch!

“It doesn’t even look like her.”

“It doesn’t look like her? It is the very essence of her!”

They asked him how he would know that.

“How would I know that? How would I know that?

HUMAN NATURE IS MY JOB!”

“Human nature? Human nature? Is that what you call it? Human nature? Well, maybe buddy, but what do you know about our mother? What do you know about our mother? What do you know about our mother? Whatdoyouknowaboutourmother!!!”

They were mindless wind-up toys.

He could not stand the sound of their voices.

“We’ve lived with her all our lives. What have you lived with? A hair brush? A broken mirror?”

He finally burst: ” I’VE WORN THE PANTYHOSE! CAN YOU SAY THE SAME!!!?”

What kind of fetishistic weirdo are we dealing with? they must surely have been thinking.

He didn’t care.

The truth is, they’d’ve fared better taking her photo to a booth on Coney Island for a three-minute chalk portrait,

and he told them as much.

They called him a narcissistic dilettante.

He called them cretins.

And once again, between artist and the

rest of the conscious world, it seemed,

there lay the abyss.

And so the family of dead Laura stormed off

with all her trinkets and whatnots,

and he walked away with no money in his pockets,

but his own Laura right there on his wall,

where no one could ever touch her again.

She was his. He was hers.

And as he sipped, not swigged this time, his shot of Old Forester,

he could not help but reflect on an Ingmar Bergman line:

I could always live in my art, but never in my life.

Angela Carole Brown is the author of three published books, The Assassination of Gabriel Champion, The Kidney Journals: Memoirs of a Desperate Lifesaver, and Trading Fours, and has produced several albums of music and a yoga/mindfulness CD. Bindi Girl Chronicles is her writing blog. Follow her on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram & YouTube.

🙂 🙂 🙂

LikeLike

Don’t ever stop writing … or painting … or singing … or creating … or being.

LikeLike