When did the value of a piece of art get determined by the hours logged? Is it me, or does that idea seem counterintuitive to the very spirit of art? That spirit is, among other conceptions, that which reflects something more than the surface thing it is made of, and that “something” has the power to entertain, enlighten, challenge, tickle, anger, transform, and the oh, so many other splendid eruptions of the human heart that art can accomplish. And to clarify “more than the surface thing it is made of” I mean that a canvas, some paint, and a brush don’t make the thing art. What makes it art is how it speaks. If it speaks. Of course, that idea is so very subjective and abstract that anything can be called art. And, personally, I think that’s the very beauty of it.

I had a conversation maybe 6 or 8 months ago with a woman who’d come to an art show that a couple of my alcohol ink pieces were in. She didn’t have a thing to say about my pieces (I knew right away that my small abstracts were not her thing; and that was a-okay with me), but she did go on and on about a piece she had flipped out over. She had been interested in buying it but was stopped by the price tag. In a nutshell, it was a painted cello; I mean an actual cello that was painted, and the imagery painted on there was abstract, but not like the large, sensuous brushstrokes of O’Keeffe, or the random splatters of Pollock. They were squiggles and lines and shapes, geometric, detailed, and meticulous. It sort of resembled code, and even a bit of hypergraphia. It was colorful, every color under the sun, it seemed. I really liked it. It hearkened to me aspects of Basquiat, Haring, Kandinsky, and even Schnabel, as there were also bits and pieces of found objects glued on, and which gave the whole thing a very New Orleans vibe, or a voodoo vibe, or a creole vibe, and I may or may not be saying redundant things. It was a compelling piece. Since the canvas was the wooden instrument itself, I figured it must have a meaning related to music, but it was such an abstract concept that I didn’t linger too long on what that might be, because when it comes to abstract art, I give up everything to the piece, my need to make sense of it, or to create some kind of order.

In any case, while I liked the piece, this woman loved it. But she was indeed bugged by the price tag. It was selling for $8000. I didn’t blink an eye, except in the knowledge that I can’t buy a piece of art for $8000 and may never be in a position to do so. So, it was a non-issue for me. If the artist believes the value of his work is $8000, and can get that, then it’s worth $8000. (For the record, I never pursued finding out if the piece ever sold, or if the artist took his piece back home with him and re-thought his price tag). The value of a thing is self-evident, as it really is determined by two things: The decision of the artist to put the piece’s value at X. And if the market bears that.

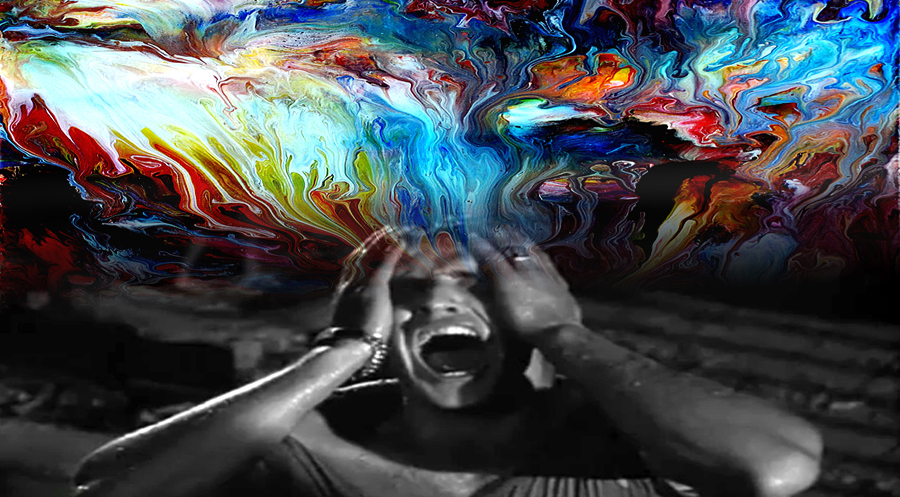

The woman begged to differ with me, and proceeded to break down what she felt the worth of the piece should be based on the number of hours at the task of creating it. She took a guess on how long it might’ve taken. And then broke down that number into dollars. I can’t even remember what the number was, because in all frankness even THAT is an abstract, since neither of us had a clue how long it took this artist to create the piece. But let’s say she came up with $1000 per hour. Is the artist worth that wage? was the bottom line for her. And the fact that she looked at it in terms of a wage was fascinating to me. I happen to believe that what goes into any artistic endeavor, from painting, to composing music, to playing an instrument, to writing a poem or a novel, to directing a play, to acting, to dancing, to choreographing, to photographing, to sculpting…..is more than the rudimentary, physical manifestations: Telling an actor to move here, take a beat there; affixing the paint onto its canvas with the stroke of a brush; mastering the physical constraints of a pirouette, typing words onto a manuscript. And it’s more than the amassing of hundreds of hours on a timesheet. First, there is the quite crucial element of the thing birthed, forming, growing inside one’s brain, then on the canvas, staff paper, dance floor, typewriter, etc., conceptualizing, determining what message or non-message this creation is. Artists are often in search of healing, which is customarily why they’ve been led to an art form to begin with. A way to offload trauma. Which means, there is the inner resonance. What is it speaking to?

The measurement of a piece: it’s size, girth, length of time it took to create, tells us little of its emotional, spiritual, cosmic impact. Really, it all comes down to one question: What does it do for your soul? The rest doesn’t matter.

That’s MY bias, of course. This woman, an art lover herself, had a different set of criteria for what something was worth, and was definitely coming from that left-brain, linear hemisphere in her assertion. Which I realized does have its place, because the deeper into the debate we got, the more I could begin to see a bit of both assertions. As there is also the Emperor’s New Clothes Syndrome. Modern legend has it that Picasso scribbled on a napkin for a waiter, as his tip for the service. And the first thought on anyone’s mind who knows this bit of modern lore is, “Get thee to an appraiser!” It’s Picasso, for God’s sake. His name alone, at a certain point in his meteoric ascent, became the thing that defined his worth. The legitimacy of that phenomenon is a whole other conversation, a more cynical, less pure one. Or maybe it’s not. Maybe this was exactly the woman’s point about the value of a thing. If Pablo had merely spat on the napkin, it probably would still have been canonized as “a Picasso.” And so, the game is played. She was challenging this artist of the cello piece to qualify his ownership of his worth. I don’t mean to say that she actually approached him at the art opening, armed with gall and too many glasses of free champagne. It was merely a whispered aside to me, posing the question: what gives him the nerve? with, of course, the inference of it’s not like his name is Picasso.

I think about my own artwork. The medium I’m presently working in is small (9″x12″). Alcohol ink on Yupo. I keep being told, “go bigger!” And honestly, at present I’m not inclined to. The reason I even qualify the size of my pieces is because this woman asked me, during this debate about worth and value, how long it takes me to finish one of my “little trifles.” I’m pretty sure she meant that as “like a sweet confection.” Nonetheless, it came off as belittling (pun intended), and I got the feeling she’s probably someone damned artful at passive-aggression, for she never lost the warmth. I responded, “anywhere from a few minutes to a few hours.” She never said a thing beyond that, but her reaction clearly betrayed, if it only takes you a few minutes to create, how are you rationalizing $100 for your pieces? I didn’t answer that question, because she didn’t actually ask it. But I did sell both my inks that evening for the price asked, and I have to admit the tiniest tinge of schadenfreude at letting her know my good news.

My alcohol inks are all abstracts, at least so far on this journey. I’m partial to abstracts. So, when a friend bought one of my pieces a few years ago, she took it to a workshop she was conducting, where she asked her attendees what they saw in the painting. She was kind enough to share with me the varied responses. Something I will treasure forever:

“Beauty in the un-manifest, infinite possibilities.”

“Core of darkness reaching out to be brought to light.”

“Nature and the outdoors.”

“Underwater world.”

“Mermaid fairy with a flower.”

“Hummingbird with the spirit of a dragon.”

and quite possibly my favorite…

“A gathering of monks.”

These answers not only moved me beyond words, but also affirmed for me what I believe is most powerful about the abstract realm—art of any realm, for that matter—that we each glean from a piece what shows up for us; what we need in the moment. And that makes something worth whatever the art lover is willing and able to pay to take it home and be moved by it every day.

The experience of art is far more than just a surface observation of: Nice colors! Nice notes! They’re in tune! Stellar spin! She must have really strong muscles! He uses pretty words! That’s gonna just about cover my giant wall and match my sofa! So how can it be quantified? The very experience of art is an intangible abstract. It can open us wide open. Give us what we need in that moment.

Or it doesn’t, and we move on.

There’s also absolutely nothing wrong with admiring a pitch-perfect note, a gorgeously rich hue, someone’s logic-defying technique or prowess. It’s just, there’s so much more experience that can be had if we don’t allow ourselves to be contained by mere surface. Surface has nice things to offer. But beneath it? Can you imagine what you might be missing if you stopped just short? Perhaps a magnificent rebirth. And therefore, again, what is that worth?

If something isn’t grueling or doesn’t take a chunk of flesh from us to create, or doesn’t take months and years to finish, or doesn’t require a vast studio space in which to contain its girth, does that mean its value is less? Or can’t have impact? Because impact is the endgame. If a work of art collides with someone, and the explosion from that collision is life-altering, or even a tiny shimmy, art has done its job.

Some of the most compelling art I’ve ever experienced is from Japanese minimalist artists known for line drawing. Matisse and Picasso did incredibly compelling line drawings. These are not the intricate layer after layer of exploding color and texture and brush skill in replicating a figurative image, which is what Picasso was known for in one of his many eras. This is the use of pen or pencil, and drawing single lines. And these “trifles” can be quite startling. Or how about: a brilliant haiku packs no less a punch than a brilliant novel. Does Blind Willie Johnson’s simple guitar and warbled voice on Dark was the Night, Cold was the Ground connect less to struggle and pain than Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima? For some, there is no difference in the connection to pain. And for someone else, hell yes, there’s a difference. Which is perfectly valid. Except the difference won’t be because the Penderecki has about 10 billion notes and a riot of tone clusters and 52 stringed instruments and is a discordant behemoth, and Blind Willie’s is merely a precious, tiny, single voice and 6 strings on an old bottleneck slide guitar. Deep, exquisite pain is felt every time I have listened to either of these heart-wrenching, power-packed pieces of music.

Size really does kind of lose its meaning when we dare to probe deeper. So, then, if it isn’t size, what is it that makes a work of art worth something? Is it, after all, the amount of labor invested and hours logged? Is it education and an MFA vs. being self-taught? Is it something completely intangible that only the person colliding with the piece can experience, because their experience will be funneled through and informed by their own history, and what speaks to them will not be replicated by any other person’s collision with the same work of art?

It is a random concept, the worth and value of a thing. So random as to be, actually, a kind of silly debate. I realize that. But thank you anyway, woman I argued with. There’s nothing more enjoyable than to exercise the critical thinking mechanism in the splash pool of wonderment. The value of a work of art is whatever the market will bear. Plain and simple. And yes, there is some wicked capitalism and sleight-of-hand opportunism often involved. I wrote a microfiction once called Supernova that I’ve offered below. It speaks to that very abstract idea of value, and just how unstable, unquantifiable, and exploitable it actually is. Enjoy my dark little trifle, and—if you even care about such things—ask yourself what you think makes a work of art worth anything.

Or just relax with a glass of wine, and stay away from us pontificators. You’re surely better off.

Supernova

He sold the painted canvas on the street for $1, a striking abstract created by his own homeless hands. Years later it sold at a gallery for $800. The original purchaser, an artist himself, had put his own name on it. By the time many more years passed, and it sold at Sotheby’s for a million (as the artist/thief eventually enjoyed astronomical fame), the homeless man, who never thought of his painting again beyond that corner sell, had long ago died, impoverished. The art thief did not fear God. He did, however, feel the dread of ghosts now and again.

— from the 100-word story collection Aleatory on the Radio